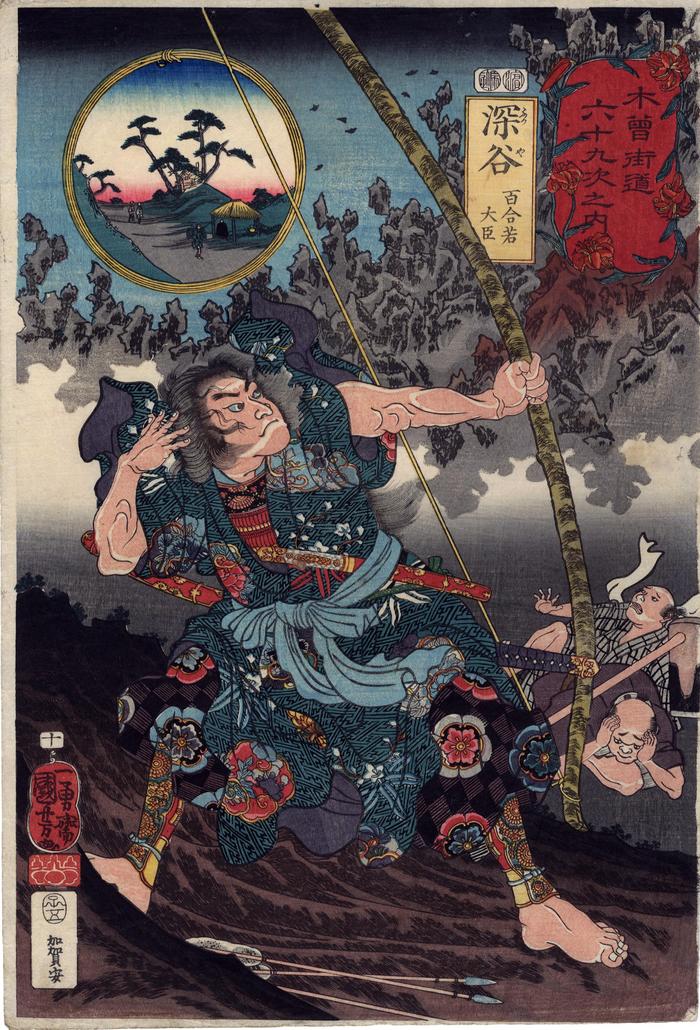

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (artist 11/15/1797 – 03/05/1861)

No. 10 Fukaya (深谷): Yuriwaka Daijin (百合若大臣), from the series Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō Road (Kisokaidō rokujūkyū tsugi no uchi - 木曾街道六十九次之内)

05/1852

10.2 in x 14.875 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese color woodblock print

Signed: Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi ga

(一勇斎国芳画)

Artist's seal: kiri

Publisher: Kagaya Yasubei

(Marks 196 - seal closest to 25-099)

Date seal: 1852, 5th month

Censors' seals: Hama and Magome

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

British Museum

The Agency for Cultural Affairs

Tokyo Metropolitan Library

Google maps - Fukaya

Musée Cernuschi "Yuriwaka Daijin is a character in kōwakami, a form of musical dance-drama (similar to nō) that was popular in the late sixteenth century. His name may be translated as Young Lord Lily, and lilies decorate the series title border. After fighting in the war against the Mongols in the thirteenth century, Yuriwaka is stranded on an island and is unable to return home for years. When he comes home at last, he has been gone so long, and is so changed by his experiences, that no one recognizes him. His wife believes that he is still alive but is unaware of his return, and she is threatened by the villain Beppu because she has refused to marry him.

In the climactic scene shown here, Yuriwaka demonstrates his identity by stringing and drawing the great bow that only he, a renowned archer, is strong enough to use. He kills Beppu and its happily reunited with his faithful wife. The inset landscape is framed with bowstrings, another reference to this episode.

As early as 1906, the writer, translator, and critic Tsubouchi Shōyō pointed out that the story of Yuriwaka is strikingly similar to the basic plot of Homer's Odyssey, which recounts the adventures of the Greek Odysseus (also known as Ulysses) on his way home from the Trojan War. Further research by various scholars has shown that the Yuriwaka story is not found in older Japanese sources but appeared suddenly in the late sixteenth century, just when Jesuit missionaries were most active in Japan (prior to the banning of Christianity in the 1630s). Moreover, the name Yuri (Lily) is very unusual for a man, but it could well be a Japanese abbreviation of Ulysses. All in all, it seems extremely likely that this tale was inspired by one of the greatest classics in Western literature and was probably written by a sixteenth-century Japanese who had heard the story of The Odyssey form a visiting European."

Quoted from: Utagawa Kuniyoshi: The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō by Sarah E. Thompson, Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 2009, p. 36. Illustrated in a full-page, color reproduction on p. 37

****

Esther Lowell Hibbard wrote this as part of her University of Michigan doctoral thesis in 1944:

"About the middle of the seventeenth century there appeared in Japanese literature a tale based on the adventures of a hero called the Minister Yuriwaka - a tale which has been retold more than a score of times since then in various forms by many writers down to the present day. In its earliest written form the tradition recounts how a childless nobleman who has prayed to the Goddess of Mercy is granted a son, whom he names Yuriwaka (Lily Youth). When Yuriwaka reaches a suitable age he is appointed Minister of State by the Emperor and is married to the daughter of a courtier. Soon afterward, following an attack upon Japan by a large army of barbarian invaders, the Emperor chooses the hero as commander-in-chief of a punitive expedition. By means of supernatural aid the hero subjugates the enemy and is on his way home in triumph when his two chief retainers abandon him on a desolate island and plot to take over his fief in Kyūshū.

When they reach the capital of Kyūshū the retainers spread a false report that their lord is dead, and at once begin to press for the hand of Lady Yuriwaka in marriage. She puts them off with the excuse that she must first fulfil a religious vow. In preparation for her retirement to a temple in order to carry out her intention she releases Yuriwaka's hunting horses and hawks. Although free, the hero's favorite hawk refuses to fly away until given a rice- ball, which it picks up and carries to the island where Yuriwaka has been abandoned. Recognizing the bird, the hero writes a message on a fallen leaf with his own blood, attaches it to the bird's leg, and dispatches the bird to the capital, where his wife reads the message and rejoices to know that he is still alive.

Some time later a fishing vessel drifts to the island, and although the fisher- men fail to recognize the hero because of his emaciated condition, they agree to take him back with them. On reaching the capital they present him as a curiosity to the disloyal retainers, who entrust him to the care of an old gate- keeper. One night Yuriwaka overhears the old gatekeeper telling his wife that their daughter had been drowned in place of the Lady Yuriwaka, who had been condemned to death because of her steadfast refusal to marry the traitors. The hero is strongly tempted to disclose his identity at once, but decides to await a more favorable opportunity for wreaking vengeance upon his enemies. The desired opportunity occurs at the following New Year, when an archery contest is held in honor of the ruling traitors, and the hero is permitted to take part. Using an iron bow which he alone can bend he kills the traitors, first having made himself known to them as their lord. He then rewards his faithful followers and receives belated honors from the Emperor for his military service."

According to Hibbard the first published version of Yuriwaka Daijin appeared in 1662.

Hibbard also wrote: "With the rise of the puppet drama in the seventeenth century, the Yuriwaka tradition passed from the pure folklore into that of literary composition. In the hands of Japan's greatest dramatist, Chikamatsu Monzaemon, it became a florid melodrama full of literary allusions and exaggerated incident, which has won a permanent place in Japanese literature as a classic."

Later Hibbard added: "...the story begins with the birth of the hero. The Goddess of Mercy appears to the hero's father in a vision, holding a budded lily in her hand, and prophecies the birth of a son in answer to his prayers. It is noteworthy that whereas the lotus flower is nearly always associated with the Goddess of Mercy in Buddhist iconography, in this case the flower she holds is a lily."

****

There is another copy of this print in the collection of the Ena City Museum. However, it is illustrated in color in Die Macht des Bogens by Johannes Haubner, p. 174. Haubner refers to Yuriwaka as the Japanese Odysseus.

****

Listed, but unillustrated, in Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, p. 190, #497.

Kagaya Yasubei (加賀屋安兵衛) (publisher)

warrior prints (musha-e - 武者絵) (genre)

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (近松門左衛門) (author)