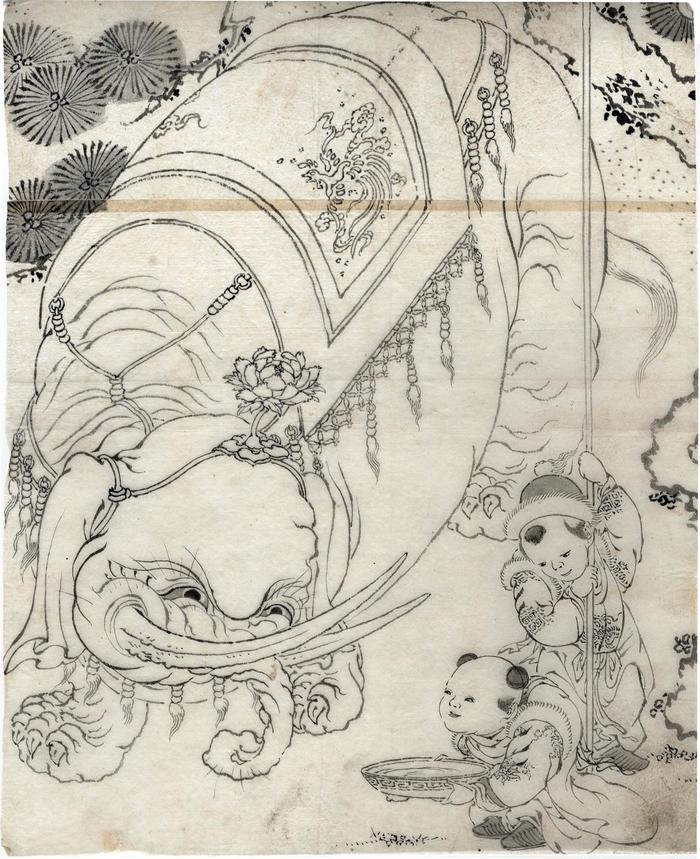

Chinese children (karako) and an elephant from the Hokusai school - shita-e (preliminary drawing)

Painting

ca 1830

9.5 in x 11.5 in (Overall dimensions) Sumi-e (painting in India ink)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston - Kiyonaga print on the same theme, ca. 1780 Preliminary drawing (shita-e) for a woodblock print. They can also be used as guides for sculptors and painters.

****

"The publisher would receive from the artist the design's preparatory sketch, called a shita-e ("preparatory picture"), which widely varied in terms of completeness or detail level. Usually, the artist would provide only the main contours for the figures and an abbreviated suggestion for a background, the details of which were filled in advance by students or professional block copyists (called hikko). Sometimes, the artist would provide drawings that were almost finished or highly detailed. The final preparatory drawing was then traced by the hikko onto very thin paper (typically minogami). This final block copy of the drawing was called the hanshita-e ("block design" or "block sketch")."

Quoted from: Ukiyo-e: Secrets of the Floating World.

****

Note that hikkō can be spelled with a long 'o'. Its kanji is 筆耕 (ひっこう) is used to mean any kind of copying or stenciling.

****

The children, i.e., these Japanese boys are dressed as Chinese boys or karako (唐子). They are wearing elaborate T'ang dynasty clothes. William Green wrote in "Treasures from heaven: children of Japan in the prints of ukiyo-e" in Andon 20, winter 1985 on page 86: "On important holidays such as the New Year, parents of means in Edo Japan togged out their little boys - we do not see girls as karako - in the plumed and tasseled hats, ornate jackets, baggy pants, and cloth slippers so typical of T'ang period Chinese court dress. Karako are the 'curious kids' of Japanese prints. Are they Chinese or Japanese? "

Tajima Tatsuya in "Karako Asobi: Images of Chinese Children at Play" in Images of Familial Intimacy in Eastern and Western Art discussed children's hairstyles in Edo period Japan. "...what about children's hairstyles? [The] child has a shaved head, with one tuft of hair left, and this hairstyle is not limited to this print. During the Edo period it was common practice to shave a young child’s head and leave one section unshaved. Indeed, the ancient custom in Japan was to completely shave a child’s head soon after birth and keep it shaven until the “growing hair” ceremony conducted when a child was 3 years old. However, by the Edo period, even after the growing hair ceremony, it was customary to shave a child’s head, leaving one tuft. Thanks to this tuft of remaining hair, this hairstyle came to be known as poppy (keshi), guy (yakko), or Chinese child (karako). The last term, karako, or literally Chinese children, is said to derive from the hairstyle worn by children in China."

"One modern scholar focused on this Chinese style of children in the Edo period, namely, Kuroda Hideo, a Japanese medieval period history scholar. Originally there was no custom in Japan for children to wear the karako hairstyle or to wear a child’s apron-like bib. Images of Chinese style karako were first brought to Japan in the medieval period, and this meant that some of the children depicted in Japanese medieval period genre scenes are shown with the karako hairstyle. However, this hairstyle was not defined as a general custom. Kuroda notes that the fashion for karako hairstyle among Japanese children did not begin until the pre-modern era, and that this reflected changing views of children. To quote Kuroda, “In the pre-modern era, the concept of ‘children as treasures’ spread in the general populace, and along with this concept, children were seen as beings to be protected given their fragile lives which could easily end and return their souls to the realm of the gods and Buddha. Hence, they became objects of affection that should be carefully nurtured, and this led to the creation of visual images of their adorable features. Given these factors, the karako can be seen as a reflection of and pictorial depiction of the pre-modern discovery of the cuteness of children.” "

****

David Waterhouse in his scholarly work on Harunobu wrote: "Karako, usually at play, were a popular subject in Ming and later Chinese paintings, and are seen occasionally in the work of several eighteenth century ukiyo-e artists, including Okumura Masanobu, Harunobu and Kiyonaga."